An official in BAPPENAS, Indonesia’s planning ministry, was quoted in a few different papers last week saying that the Indonesian government wants to promote what they call public private people partnership (P4), by giving people that are resettled ownership in the toll roads replacing some portion of their cash compensation. Is this policy a good idea?

In short: no. It is a truly, truly terrible idea.

It doesn’t solve the core dispute

Land acquisition is slow in Indonesia because people either don’t want to move at all, or they don’t like the price being offered for their land. Let’s say you’ve got some guy, Mas Joko, that you have offered IDR 100 million for his land, which he has rejected. “OK”, you say, “how about we offer you shares instead?”

Of course Mas Joko’s first question is going to be “what’s the value of the shares?”

If your valuation of the land is IDR 100 million, then that’s the value of the shares you’re going to offer him. In which case, why should he view the offer any differently?

If you decide that you can pay him more in shares than you can in cash, say, IDR 150 million, then if that is indeed the true value of those shares, you are actually paying him IDR 150 million in cash because you could have just sold the shares on the market yourself, then paid him IDR 150 million in cash. If you couldn’t have sold those shares on the market for Rp. 150 million, then that isn’t the value of them and you’re trying to scam Mas Joko.

Paying people in equity doesn’t make the process of negotiating the value the land any easier; which is the core problem.

Poor people will not be able to (and should not) use it

The risk and cashflow profile of equity in a toll-road is dramatically different from cash.

Let’s try and help Mas Joko try to choose between IDR 100 million in cash and IDR 100 million in equity in the toll road company. He’s not a rich man. He’s got a small plot of land that he inherited from his father, with a house that he lives in with his wife and two kids. Whatever he accepts, he’s going to need to find suitable housing for his family pretty much immediately.

With IDR 100 million in cash, he can go any buy another place straight away and, hopefully, live his life much as he was living it before he got resettled. Let’s look at how his life might be different if he were to take the equity.

The first thing you need to know about equity is it only pays out money if the company pays dividends, which only happens if the company is making a profit, which can only come when the company starts operating and everything is going smoothly.

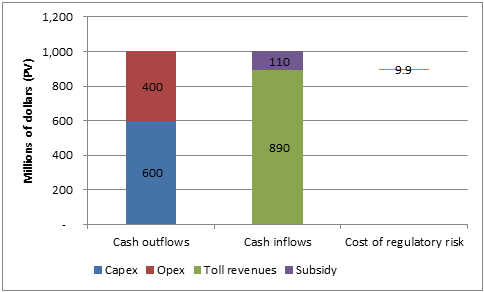

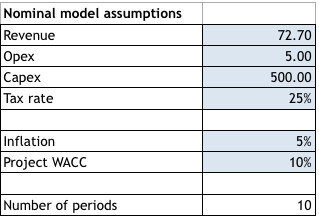

So, lets look at the cashflow profile first. If he takes the equity, Mas Joko will need to wait until the rest of the land acquisition is done, then for the construction to be completed and the road to start operating before he has any chance of getting any cash at all. Looking at the Cikampek-Palimanan toll road that just started operating last week, land acquisition took 6 years (which is unusually long), while construction took 2.5 years (which is about right). Even assuming land acquisition will now be a breeze with their genius new policy, Mas Joko will need to wait at least 2.5 years until he has a chance of getting any money.

What is he meant to do in the meantime? Where will his family live? They haven’t got the capital to buy a new house because it’s all tied up in shares, so they’ll need to rent somewhere. Do they have the income to afford to rent? Previously, their housing was “free” (zero marginal cost) because they already owned their house, so the entire family income was available for non-housing consumption and savings. Now they have to find enough room for rent in that family income, so—assuming they can even afford it—either their consumption or their savings will suffer.

Equity is also dramatically different to cash in its risk profile. Cash is pretty close to zero risk. As long as it doesn’t get stolen and your bank doesn’t go belly-up, it goes straight to your bank account and stays there, accruing interest until you find something to do with it. Equity in a greenfield toll road is a completely different ballgame.

The BAPPENAS official was quoted by Kompas as saying “every big project that involves the private sector is usually always profitable.” This is patently untrue. Toll roads with demand risk, in particular, have been performing very badly over the past few years. So many were going bankrupt (meaning the equity holders lost part or all of their money) that the Australian government asked the Productivity Commission to conduct an inquiry into the financing of infrastructure to see what needed to be changed in the industry. Closer to home, the MNC group don’t sound like they are very happy with their investments in the toll road sector. By taking an equity position, you are taking on the risk that the cashflows you might get from the project will be delayed, or may even not materialise at all.

One of the ways in which poor people are fundamentally different to non-poor people is that they’re much closer to the bankruptcy line at any given point; they’re severely constrained in their liquidity. A single shock, like a family illness/injury, or a drop in income can be disastrous. As a result, they become incredibly wary of anything that harms their liquidity or increases their risk exposure. In fact, this proposal to give people equity instead of cash both harms their liquidity and increases their risk exposure! No poor person would (or should) take equity over cash.

Calling this a P4 and talking up the benefits for the people is a joke. The only people that would even remotely consider taking this up would be the richest of the rich, big companies, or government entities. No poor person would take it up, let alone be guaranteed to benefit from this.

Implementation would be a nightmare

I have already dealt with the problem of valuation above. Even assuming you get everyone’s land valued appropriately and converted into equity, they now become part-owners of the project. How do you integrate their rights and responsibilities as minority shareholders into the project going forward? How do they make sure that the project is distributing dividends in the way that they want? How do they make sure that the board, that is responsible to them, acts in the way they want? How do they make sure they don’t get forced out, diluted, or otherwise screwed by the dramatically larger shareholders?

Indonesia does have minority shareholder protections built into law, but in practice, they’re very hard to enforce, and doing so costs a lot of money in legal fees. Will the people that take this equity have the time, money and understanding to mount a legal defence if they feel like they are being mistreated?

Then, if you are protecting the minority shareholders, how do you make sure that the company can still operate? Indonesia’s banking penetration is currently around 20% to 30%, depending on who you believe. Most likely these minority shareholders aren’t going to be the most financially savvy investors ever. It’s not fair to expect them to provide meaningful oversight, and it’s not fair to the company to feel like they have to explain every decision to hundreds or thousands of people that have most likely never heard of the concept of corporate governance.

Also, part of the benefit of getting the private sector involved is that they bear the risk if they go bankrupt. If the toll road were to be in trouble, would the government let it go bust, taking away the savings of the poor minority shareholders with it, or would they bail them (and the private company, whose incompetence led to the problems) out?

This sort of thing is immensely complex, and if there’s one thing the government of Indonesia doesn’t need in its infrastructure agenda it’s more complexity. Let’s do some simple projects first before trying to solve something as complex as the protection of minority interests.

In summary

This proposal will not solve the problem. Land acquisition is hard, but the solution is not to come up with ever more complicated schemes and try and give them catchy names that sound like they are benefiting the poor. The solution is to deal with people fairly and firmly, and the existing regulations, while not perfect, are adequate for that purpose. Indonesia is facing an infrastructure crisis, and the government’s endless tweaking of regulations and a lack of focus on actually delivering projects is a key part of why.

All of the quotes about this policy seem to have been from a single event, hopefully it was just an off-the-cuff comment that will not actually see implementation. I am certainly hoping so, and looking forward to seeing more progress on real projects.