When you build a financial model, there are two ways you can manage your numbers: real, and nominal. In real models, you pick a base year, and do all your calculations using constant real dollars, rupiah or whatever currency you’re working in. In nominal models, you need to adjust all of your numbers by the relevant inflation figure.

Whether you use real or nominal is largely a matter of personal taste. They are (or, at least, should be) mathematically equivalent. It’s more a matter of presentation. I have always been a bit of a nominal model man. The first professional model I ever took over from someone was a nominal model, and I guess that shaped how I think about these things, but, at least theoretically, I don’t mind much which flavour you want to use.

I said “at least theoretically”, because in practice, I have had lots of problems with real models. In fact, a significant number of the real models I have come across in my professional career have had the same glaring mistake. Take a look at the simple models below and see if you can see what it was.

Let’s imagine you work for the government and your boss wants you to analyse an infrastructure project to find out how much a private party will charge users to provide the service.

The project will operate at full capacity for a 10-year period providing a service for which it charges a tariff and incurs operating expenses that both increase with inflation. The business is pretty capex heavy and the capex is all incurred in the first year of operations, then depreciated on a straight-line basis over the 10 year operating period. You’ve got some cost estimates, and a pretty good idea of what the weighted-average cost of capital is for businesses in this industry, so you put all the costs in and run a goalseek to get your full-cost-recovery tariff.

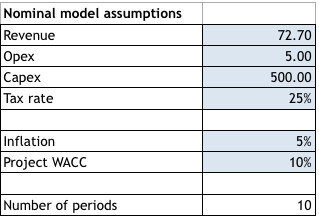

First you make a real model (but unknowingly, make a mistake in its design). See below: