I'm not sure how I missed this (or how the English, and Indonesian language media also seems to have entirely missed it at time of writing), but the Bandar Lampung Bulk Water Supply public private partnership ("PPP") project pre-qualification has been open since 30 March, and is open until 30 May 2017.

Source: PDAM Way Rilau

It's odd that this isn't bigger news because, as far as I am aware, this is the first PPP project to be tendered since the Palapa Ring projects were tendered in late 2015

This is the second time this project has been tendered, and the previous go-around was quite a big deal.

What happened last time

The previous tender process was launched in 2012, and attracted substantial interest from domestic and foreign bidders, with 10 consortia submitting bids. Shortlisting happened fairly quickly, with Water Consortium (Hyundai Engineering and Construction, Itochu Corporation and PT Potum Mundi Infranusantara); Abeima and PT Wijaya Karya Persero Tbk; Acuatico and Mitsubishi Corporation; and Manila Water and Great Giant Pineaple Co forming the final four.

Yet, disagreements over the project costs; the allocation of those costs between the users, central government, and city government; and the project structure meant that the final request for proposal was substantially delayed.

The issue of the project costs was arguably the most critical issue, with widely diverging capital costs proposed by different parties within government. The Ministry of Finance allocated a maximum subsidy based on the lower estimate of the capital costs--allocating a maximum subsidy of IDR 350 billion--and the project went to tender in September 2015.

The Ministry of Finance's estimate of the required subsidy proved to be excessively conservative, and none of the bidders ended up submitting conforming bids, resulting in a failed tender.

Why did no one submit a conforming bid?

Indonesia's main way to provide subsidies to infrastructure projects is through what they call Viability Gap Funding ("VGF"). The aim of this VGF is to bridge the financial "viability gap", allowing government to engage the private sector to deliver a project that they otherwise wouldn't be interested in. (Note: there's a lot more to say about VGF, and why, and when it should be offered, but that's a for separate blog post sometime.)

Indonesia's VGF guidelines are interpreted to mean that VGF is not allowed to exceed a maximum of 49% of the capital cost of a project. This means we that, based on the announced IDR 350 billion VGF, the government was assuming the capital costs for the project were IDR 700 billion (with a little rounding).

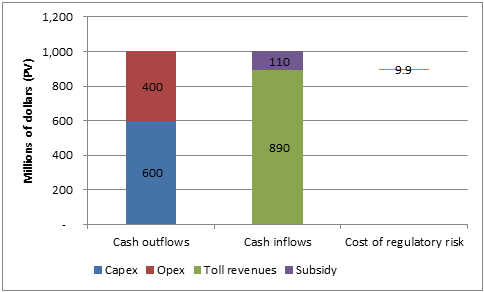

The graph below illustrates how the tender failed.

In this project, the revenues from PDAM are fixed*, the bid factor becomes the minimum VGF required to deliver a project that can fulfill the technical specifications. Whichever bidder gets the optimisation of the lowest capital, operating, and finance costs, should be able to offer the lowest required VGF to do the project, and win.

The Owner’s Estimate column showing project costs of IDR 1.4 trillion is present value terms, and equivalent revenues shows a simplified version of the project cashflows that illustrates how the government arrived at the IDR 350 billion VGF number. For this simple illustration, I’m assuming that the total operating expenditure over the life of the project is the same as the capital expenditure. If someone feels like giving me a copy of the government’s owner’s estimate financial model, I’ll happily update the figures, but it doesn’t really matter for the illustration.

The Government’s Ideal Scenario shows what the government was hoping for, where some party ideally was able to get the project done for less than they estimated, and would bid with a VGF of less than IDR 350 billion.

The Actual Lowest Bid shows what actually happened. The bidders would have been working their hardest to get the lowest capital, operating and finance costs to decrease the VGF required to meet their costs, and get under the government’s cap, but none of the four was able to do it. So, the tender failed.

Failed tenders are really expensive

The failure of the Bandar Lampung Bulk Water Supply Project destroyed a lot value in the Indonesian economy; for the government, for the bidders, but--most importantly--for the citizens of Bandar Lampung.

On the government's side, they had multiple rounds of advisers, including top-shelf (and quite expensive) commercial, legal, and technical advisers, both for the preparation of the transaction, and for the appraisal of that transaction. In aggregate, the fees paid to these advisers would be well into the millions of dollars, and I'd be surprised if it were below USD 10 million. Beyond the fees, there is the wasted time of all of the civil servants, all the way up to the minister level, in multiple ministries and agencies, who had to participate in meetings, and produce their own analysis and recommendations.

For the bidders, participating in tender processes is also expensive. Preparing a pre-qualification submission can easily run into the multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars each in staff time and advisers' fees to make sure they can do the project, and to prepare the documents in the format required. Then, the shortlisted parties easily blow another couple of million dollars to prepare a conforming bid, including their preliminary designs. With 10 pre-qualification submissions, an extended pre-bid process, then four short-listed bidders, there would easily be another USD 10 million dollars of value wasted there.

Finally, and most importantly, the citizens of Bandar Lampung have had to go another five years without adequate water supply as a result of these delays, wasting money buying water from eceran, wasting time boiling water and otherwise creating plans to make sure they can access potable water as and when they need it, and bearing health and lost productivity costs due to the poor quality water.

Source: Statistik Kesejahteraan Rakyat Kota Bandar Lampung 2016, table 6.6, page 100

As it is, only around 20% of Bandar Lampung's 1.2 million citizens have access to piped water for cooking, or washing, and pretty much all other potential sources are worse than PDAM supply by some metric; either more expensive (private wells with jetpumps), take a lot more time (wells), or are much lower quality (unprotected wells). Although, on the other hand, most of them are more reliable.

The estimation of economic benefits of infrastructure projects is always hazy, with lots of uncertainties, but we can come up with a ballpark figure using some simple arithmetic.

The original project was for a 500 litres-per-second facility, aimed at serving 44,000 households. This is far less than the 960,000 people currently without service in Bandar Lampung, so we can assume 100% take-up pretty quickly. So, 44,000 households went with poor quality water for 5 years. If we assume the costs of the poor quality water are a dollar a day per household (counting all the wasted time, purchasing of bottled water, health impacts, etc. etc. that's certainly too low), that's already USD 80 million.

So, just as a conservative ballpark estimate of the cost of the delay, we can get to USD 100 million pretty quickly. Suffice to say that the costs of inaction are really high, and orders of magnitude higher than a couple of millions of dollars of VGF.

What has changed this time?

The word on the street is that the project has been rescoped, and redesigned to make it deliverable under Indonesia's current PPP framework. Just from the details available in the Request for Pre-qualification document on the PDAM Way Rilau website, we can see that there have been some changes made.

The raw water intake is now 825 litres-per-second, and the water treatment plant is 750 litres-per-second, up from the 500 litres-per-second of the last go around. The extra volumes mean that there are potentially more revenues to go around, to decrease the required VGF.

However, the capital costs of the project still seem to be estimated at IDR 700 billion. I'm not entirely sure how the plant capacity increases, and the capital costs (that were already proven to be too conservative) stay the same, but I'm no engineer, so what do I know? It's possible that they have found efficiencies in other areas, or are trading off capex for opex.

If you want in, you'd better hurry up

The pre-qualification process is open for another two weeks from today, so if you are planning on bidding, you'd better get on it!

* Technically not correct, but effectively the same. There was a fixed payment to cover the capital costs, and a variable payment to cover the variable costs of operation. This aims to ensure there is no economic profit (or loss) coming from the operation of the facility if the contractor performs satisfactorily.