I was reading this article on Vox by Ezra Klein and I was absolutely floored by this line:

“A lot of pundits…have a sort of Underpants Gnomes theory of Marco Rubio’s chances. Step one is Rubio is the only acceptable nominee to Republican elites. Step two is ... something. And step three is Rubio wins the nomination.”

If you’re not familiar with the Underpants Gnomes, they were invented by the creators of South Park, and appeared in the episode Gnomes; which is helpfully summarised on the Wikipedia page.

In the episode the Underpants Gnomes have a plan to make profit which consists of three phases, set out in the screenshot below:

If you can't see the image above it says:

Phase 1: Collect underpants

Phase 2: ?

Phase 3: Profit

Klein’s usage in his Vox article was the first time I had seen reference to an Underpants Gnomes theory of something, but, apparently its use in analysis of policy and political economy goes back quite a way. Forbes has a nice article that explains its applications to political economy.

Basically, the Underpants Gnomes have a view of the world that links the collection of underpants to profit via some mechanism that they can’t explain, and likely doesn’t exist. When I saw Klein use it, I was struck by how powerful and widely applicable the idea can be.

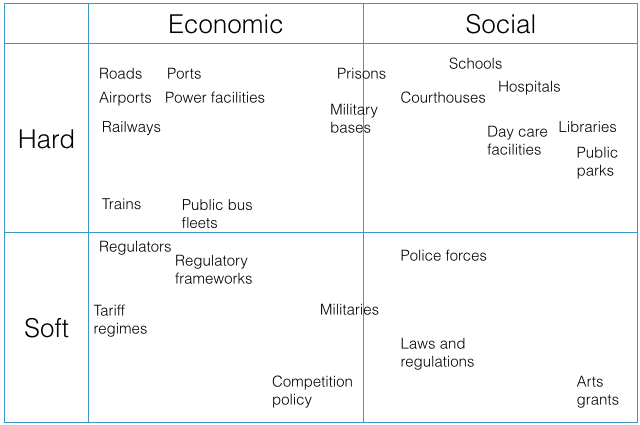

For example, in Indonesian infrastructure you see this kind of thinking.

Phase 1: Make a speech about how Indonesia needs USD 450 billion of infrastructure investment between 2015-2019.

Phase 2: ?

Phase 3: Indonesia gets all the infrastructure investment it needs

We have been in Phase 1 for the last three years, and haven’t yet seen any evidence that infrastructure investment is accelerating at the rate needed.

Another example could be from PPP.

Phase 1: Create PPP policy framework

Phase 2: ?

Phase 3: Indonesia has dozens of PPP projects

We have been in various stages of Phase 1 for a decade now, give or take…

I certainly don’t want to give the impression that Phase 2 in either of the above plans is easy! Most of my career has been spent trying to figure out exactly what they involve (after a decade, I do have some partial theories…).

The general point is that a plan needs to do more than identify a problem, and a desired outcome. To really effect change, you have to follow the thinking process all the way through.

I don’t know about you, but I plan to add this idea to my policy analysis toolkit! Now I just have to think about how I translate it into Indonesian for the first time I pull it out in a meeting with my government counterparts…