In this table, cells that are red mean that you’re highly likely to see streaks this long, yellow means you’re about 50-50, and green means you’re pretty safe.

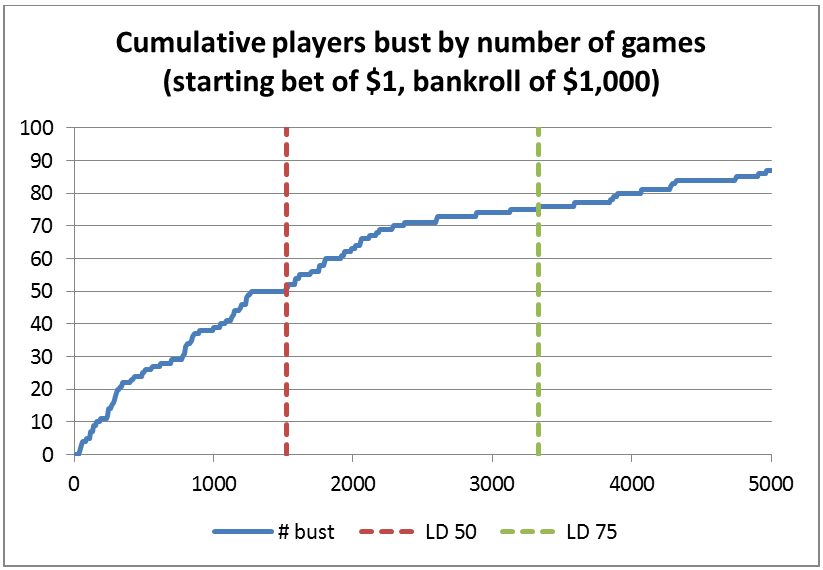

If you’re playing with a bank of a million dollars and you play 20,000 games (about a month, full-time, by my count), you’ve got a bit over a 4% chance of losing your full million dollars… Does that sound like a safe bet to you?

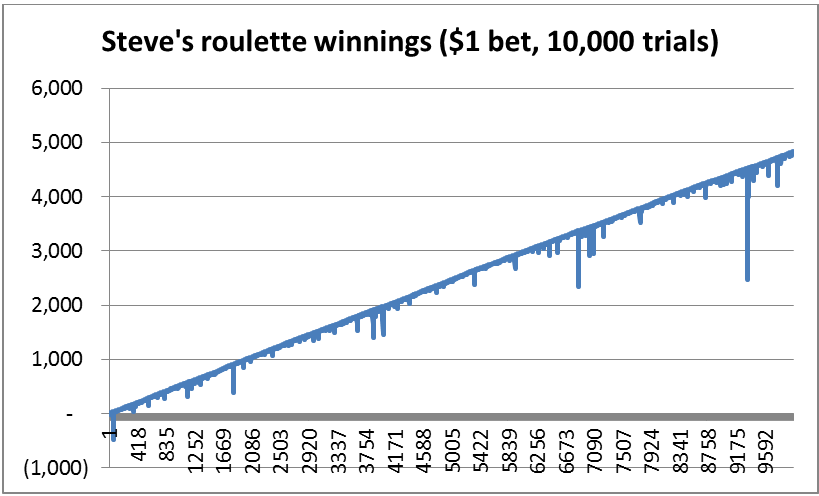

So, if that’s the risk, what are the returns? For Steve and his mates, the average return they got is negative $656. So, let’s look at the guy that did the best. He came out with $3,439 in the bank, or a net gain of $2,439. Not bad for a week’s work, but he also suffered through around an 87% chance of losing that money.

That doesn’t sound like a very good deal to me.

In fact, you’d get better odds just betting the whole $1,000 on black, then, if you win, betting your $2,000 on black again. In that case, you’ll get $3,000 profit if you win, and “only” a 77% chance of losing your money. You also get to spend your week doing something more fun than staring at a roulette wheel in a soulless casino.

In summary, yes, Steve’s system can make you a small amount of money, but it carries with it an unacceptably high risk for the potential reward.

So what?

So what? Well, most of my readers probably aren’t the type to think that they can beat casinos, so why am I spending all this time debunking stupid roulette strategies that have been debunked hundreds of times**.

I generally blog about infrastructure and public sector issues, and this sort of thing has pretty profound implications for the sort of long-term ventures that governments are required to enter into as a part of their regular course of business. If a government and a private party agree to build a power plant and operate it over a 30 year period, the risk of a major earthquake occurring on any given day is very low, but the chance of one occurring over a 30 year period might be extremely high; especially in a place like Indonesia, where I live. Other low probability, high-impact events include things like currency shocks, demand shocks, civil disorder, and so on.

Arrangements like our friend Steve’s roulette strategy are what people like Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls a “fragile system.” That is, it’s a system that works, and looks great at first, because it works the vast majority of the time; but when it is tested by extreme events, it fails catastrophically.

This is also an example of something I wrote about in an early blog post, where I urge readers to balance quantitative analysis with an understanding of the real world, and I said “there’s nothing more dangerous than a genius with a model.” Not that Steve is a genius, but to someone with little understanding of statistics, he might sound like one***.

Lessons for the real world

So, what can we learn from the experience of Steve and his mates that we can apply to decision-making in business and government?

- When you build a system, don’t ignore the low probability events; especially when your system is expected to be long-lived.

- Just because something seems to be working for someone in the short-term doesn’t mean it’s a good system.

- If someone is using fancy mathematics to make an extraordinary claim, be extremely sceptical, and make sure you do your own homework and understand it before putting it into practice.