I really enjoyed this article by Liam Boluk from REDEF It's full of fascinating insights, data and analysis about the state of the music industry and how the revenue models have been changing over the past few decades.

This might seem to be of peripheral relevance to the general sort of infrastructure economics that I post on, but a lot of the hard problems in economics are in pricing. You come across similar issues thinking about how you split costs and revenues fairly between producers, users and distributors whether you're talking about music, mangoes, medicines or megawatt.hours.

I think my music spend would roughly follow the trend seen in the graph above, but that might change, since I just signed up to Apple Music and think I'll stick around. As that will probably crowd out most other spending on recorded music I'll do, I doubt we'll see my trend line return to the lofty heights of the early 2000s, when CDs were probably my biggest single expense after rent and food, but it will be more than I have spent in the past few years on recorded music.

One thing I really like about the streaming model is that payments are more proportional to use than the more traditional album sale. Notionally, the value that I get from music is probably pretty much proportional to how much I listen to it, but with the old album model, I pay pretty much the same whether I listen to something once, or thousands of times. So, someone like Merzbow, whose album I listened to maybe 5 minutes of one time will have gotten about the same amount as, say, Ben Folds Five, whose album Whatever and Ever Amen was the first CD I ever bought with my own money and listened to on repeat for years. If you look at it per play, Merzbow probably got thousands of times more money out of me than Ben Folds Five did. Streaming reverses the proportionality, meaning, going forward, artists I listen to on repeat over the next decade will get money over that whole period, rather than just the one hit.

The big (and legitimate) complaint, of course, is that the payments per stream are minuscule. Boluk's article sets out the depressing math: "The average Spotify user, for example, listens to more than 1,300 tracks per month. When consumption is that great, the value of any one stream becomes slight. The economics bear this out: if we focus exclusively on Spotify paid subscribers ($9.99/month), the implied value of any one stream was $0.0076 in Q1 of 2015."

As Boluk points out in the article, a lot of that might have to do with Spotify's free model. Spotify's free (ad-supported) model is good enough for the majority of their users, so the only people that get pushed into the $9.99 per month group are the heavy users. My guess would be that my use would be quite a bit less than 1,300 tracks per month, but I still consider the access a pretty good deal.

If streaming services and willingness to pay for them becomes more mainstream--meaning the average user will consume less on average--then musicians will both get more listens, and more valuable listens.

How much does streaming diversify the recipients of music revenues?

Boluk spoke a bit about how the new revenue streaming model is diversifying the recipients of music revenues; meaning that the pie is shared more equally than it was in the past. As an example, in touring, he says that "in 2000, the Top 100 tours (which included ‘NSYNC, Metallica and Snoop Dogg & Dr. Dre) collected nearly 90% of annual concert revenues. Today, that share has fallen to only 44%."

It seems plausible that the same happens with streams. When I bought CDs in the 90s and 2000s, my consumption was very lumpy. If I really liked two artists, but only had enough money for one album, one would get the whole lot, and the other would get nothing. Bigger artists had bigger pull factors, so more often, their must-have albums would sop up people's album budgets, leaving the little guys out in the cold. These days, you can just listen to both and revenues will flow to them.

Boluk posted a diagram that helpfully illustrates Spotify's royalty model, which I reproduce below:

Source here, from Liam Boluk

Boluk identifies a few problems with it, but concludes that it's largely sensible; or at least, a it represents a least-worst option.

On the subject to diversifying the recipients of revenues, I noticed that, in fact, the way the payment mechanism is set up penalises niche artists in favour of big artists.

How Spotify's royalty mechanism makes small artists subsidise big artists

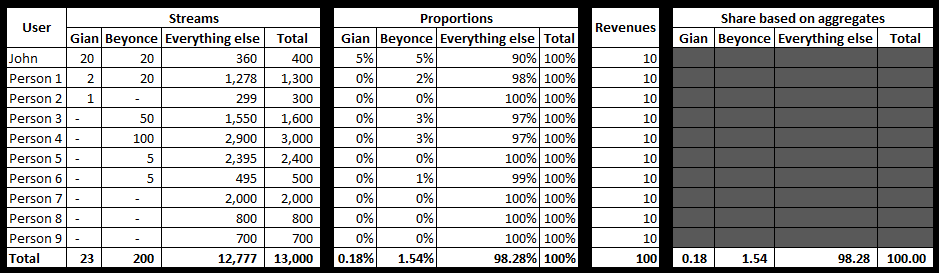

Last month, I'd guess that about 5% of my streams went to Gian Slater, while another 5% went to Beyonce, and the rest went to other music. If I was signed up to the Acme Music Streaming Company, and I was one of 10 customers, all of whom were charged $10, and AMSC followed Spotify's royalty model, the revenue splits out to the artists (ignoring label fees) could look a bit like the below:

So, you've got someone like me that listens disproportionately heavily to Gian, a pretty niche artist, and Beyonce, a mainstream artist. My listens are aggregated up with everyone else's then each artist's share is multiplied by the total revenues received to get their revenue shares.

But, there's another way this could shake out. Imagine what would happen if, instead of aggregating all of our plays together, everyone's revenue split out depending on who they listened to. See what the revenue shares based on the same number of streams could look like below:

In this case, Gian gets a whole lot more money. Why is this?

It's because when everything gets aggregated, even though I'm a heavy Gian Slater listener, my listens are only a drop in the ocean of everyone else's total streams.

So, if you're the kind of person that likes to listen to niche artists and wants to think that you're benefiting them by streaming them, well, you are, very slightly, but with the way that music tastes aggregate most likely more of your money is going to Insane Clown Posse than is going to all of your niche artists combined. If your music spend would otherwise have been on buying albums of your favourite niche bands, then stopping doing that and listening to them on a music streaming service like Spotify is probably losing them money.

It's interesting that smaller artists get screwed to the benefit of big artists, because, if anything, you could perhaps even argue that a large catalogue of niche artists is a driver of which service users sign up to. In the "which music streaming services should you sign up to" articles I read a few years ago the last time I considered signing up to one, a standard test was to see what proportion of obscure indie bands obscurest tracks were available. Until big artists start signing exclusive deals, niche artists will drive sign-ups for a small but significant proportion of people, even if they never end up listening to them!

I'd welcome critiques from people that know more about the industry, but I don't really see any way in which aggregation more fairly represents the value that users individually get from the service.

Why don't streaming services split out revenue by person?

The short answer is: I don't know. I don't know remotely enough about the way the music industry works to say. My expertise ends at critiquing payment mechanisms and the incentives created by them. I'll hazard a few guesses, but you're better off reading people like Liam Boluk for the real industry knowledge.

My number one theory for why they don't do it is that it would be a pain in the arse. Aggregating is simpler computationally, but it's also simpler for artists to understand and for auditors to check. If you're sending an artist a royalty cheque, it's much simpler to just aggregate revenue flows and stream shares, then multiply one by the other. The top-line revenue figure can just be checked against the revenue numbers that come out in their quarterly financial statements. A royalty cheque based on person-by-person streams would be much more complicated.

It's possible that the industry bigwigs that negotiated the deals negotiated them on behalf of their big fish clients, and were happy to grab money off the small fry artists, but who knows?

This stuff is complicated

Designing payment mechanisms is not easy. People always think that there's some "best practice" formula that economists should just go an look up in a textbook, or that we can derive by just looking at some data.

The best option, or usually least-worst, is always going to be a subjective call about how you trade off the desires of one group of stakeholders against another. At the end of the day, you've got to make a call and you're always going to end up screwing someone.

Still, how you design these payment mechanisms really does literally shape the industry. In addition to looking at the aggregate, it's always important to understand the impacts on particular sub-groups of stakeholders.