In English, we have a saying: if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys. A similar one is: if you buy cheap, you get cheap. In short, it means, if something is cheap, there’s probably a reason for it, and that reason may be that the quality is poor. In Indonesian a similar distinction is made between murah meriah (cheap and cheery), and murahan (cheap and nasty).

The problem is, the converse is not always true. High price doesn’t necessarily denote high quality. The only thing worse than paying peanuts and getting monkeys, is paying real money, and still getting monkeys! There are plenty of examples of this, including bottled water in places where tap water is perfectly drinkable, or where people drink expensive wine at all.

So, when I was looking at the helmets I wanted to buy a quality one, I was wondering: would I be paying for true quality, or for the illusion of quality?

Government regulation to the rescue!

Helping consumers get what they pay for is one of the things that almost everyone can agree is the job of government. Even the nuttiest of small-government libertarians accept that we need a government to protect against fraud. Well, maybe not the nuttiest ones...

In the absence of a government holding people to account for misrepresenting the quality of motorcycle helmets, you have to expect that there will be unscrupulous firms misrepresenting the quality of their helmets, if there is a dollar to be made doing it.

In a world were fraud is unprosecuted, the money transferred to fraudsters, and the time and money spent by individuals trying to verify quality for themselves with only the tools and knowledge available to them as an individual represents a market failure. It is cheaper and more effective for some sort of centralised body to set, test, and enforce standards. The centralised body doesn’t necessarily have to be a government, there are cases where industry associations perform this function adequately, but in many cases, people are sceptical of an industry’s ability to regulate itself and government oversight is required.

My lack of certainty in the Indonesian motorcycle helmet industry’s ability to deliver me a quality helmet at the right price is due to my lack of confidence in what development economists call Indonesia’s instutions.

Institutions have been arguably the hottest topic in development economics for the past decade or so. This paper by Acemoglu (one of the key proponents of the idea), Johnson and Robinson gives a comprehensive treatment, while this one from the World Bank, also by Acemoglu and Robinson, gives a slightly updated view. Ha Joon Chang takes a slightly more sceptical view here, but his scepticism is more about the policy recommendations of people like Acemoglu than the idea that institutions are important.

The big idea of instutional economics is that poor countries aren’t poor because they haven’t got any money (or, at least, it’s not just that), a large part of why they are poor is because their institutions don’t let them use what resources they do have efficiently.

In Australia, I wouldn’t have such a big problem, because we have a range of institutions in place that set standards for motorcycle helmets (Standards Australia, here), and test them (the delightfully named Consumer Rating and Assessment of Safety Helmets, or CRASH), and punishes companies that either sell or manufacture helmets that don’t meet standards (the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, or the ACCC, here). They’re not perfect, but they have been doing it long enough and competently enough that retailers and manufacturers of motorcycle helmets (and other providers of goods and services) have a reasonable degree of certainty that they will get in trouble if they fundamentally misrepresent the quality of their product.

In Australia, relatively secure in my trust in our institutions, I’d just buy the cheapest helmet that met the standards, and be on my bike. From what I can see, it seems like the cheapest ones in Australia retail for about AUD 100, or around IDR 1 million.

In Indonesia, some of these institutions exist, such as the Badan Standardisasi Nasional, and the Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Indonesia, and the Komisi Pengawas Persaingan Usaha, but I don’t think it’s too unfair to say that your average seller of cheap helmets on Tokopedia doesn't worry too much about the wrath of any of those institutions.

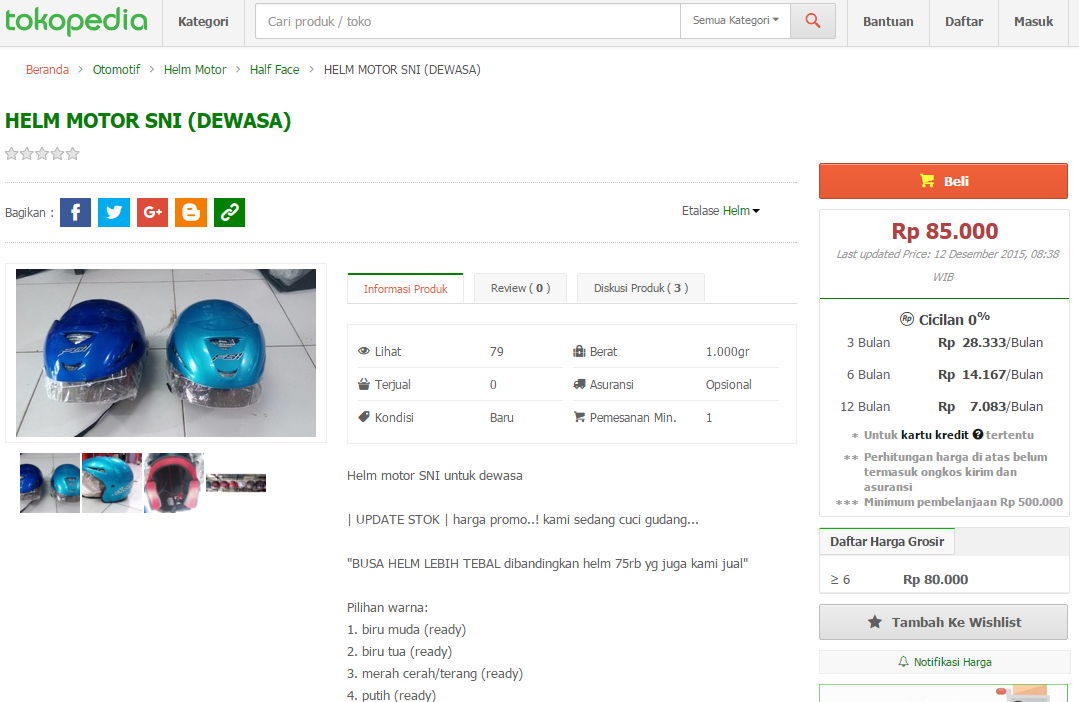

In Indonesia, standards do exist for helmets set by the Badan Standardisasi Nasional and, in theory, all that meet those standards should have an SNI stamp on them. Despite this, there are plenty of helmets for sale on Tokopedia, and through plenty of other retailers including major hardware stores and grocery stores that claim to have SNI helmets for sale for IDR 100,000 (AUD $10), or less.